Two Sides

There are some who earnestly believe that the New Testament has been reproduced perfectly in English, to the extent that there are absolutely no questions regarding the authenticity and accuracy of the text. In their eyes, the English version of the New Testament they hold in their hands is perfect in the sense that it cannot be improved upon.

There exists another group who believe that the New Testament has never been perfectly reproduced in English (nor could it be) because of its inherent unreliability and errant nature. In their eyes, the New Testament they hold in their hands cannot possibly reflect what was written 2,000 years ago because those original writings have never been recovered.

The two groups above often go head-to-head trying their best to convert others from the opposing side. As a result, it’s often assumed that there are only two honest and worthwhile points of view to hold regarding the New Testament we use and read in English today.

Mercifully, to those who have problems with both sides, there exists a third way.

The Third Way

Must one either believe that the New Testament in English today cannot be improved upon or that there’s no way for the New Testament today to hold true to what was originally written?

No.

In fact, the third way of viewing the New Testament provides a firmer foundation. It provides a foundation upon which one can place their trust in the reliability of the words they read because it deals with the truth as it is, not the truth as some would like it to be.

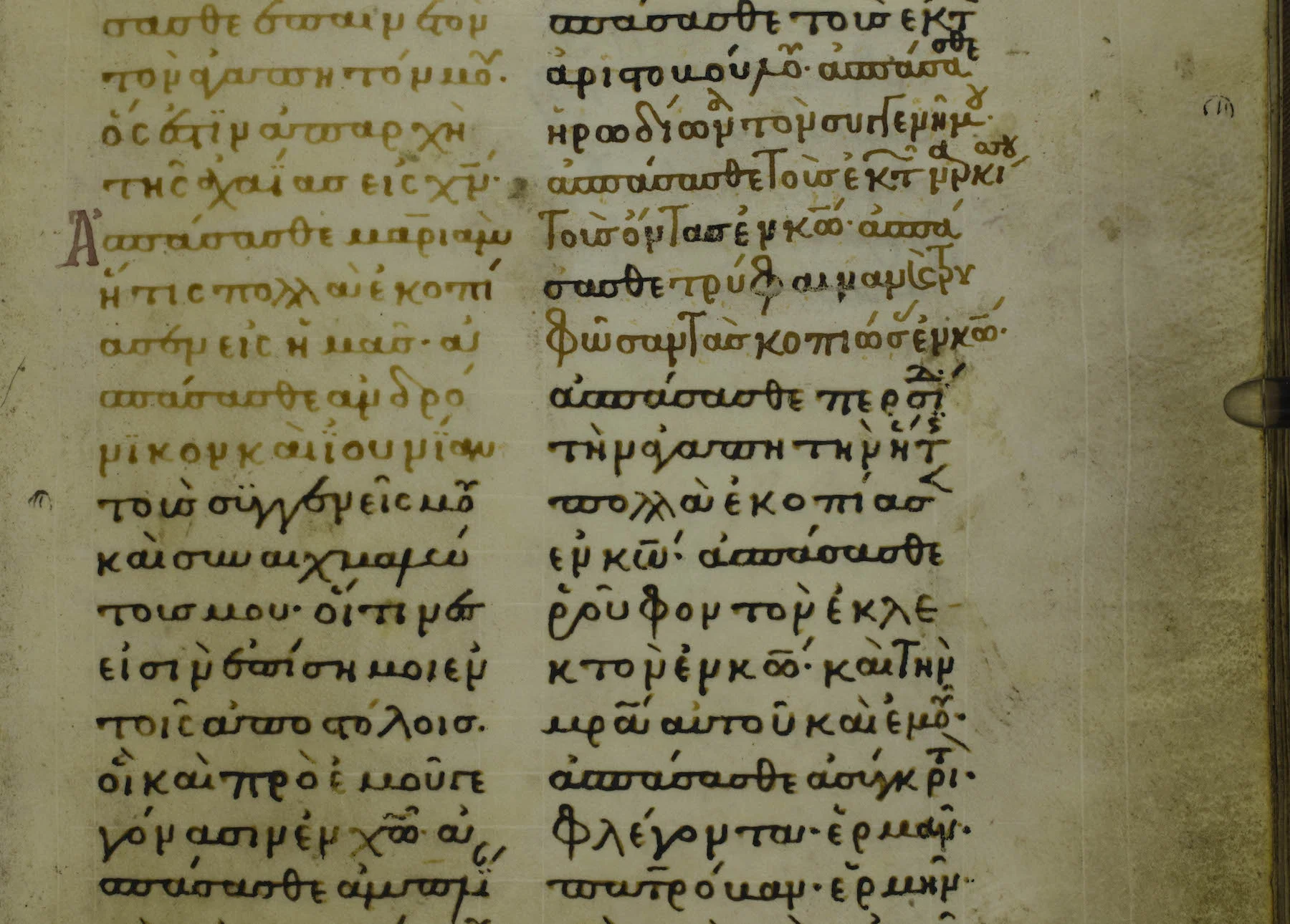

Within the third way, the New Testament reproduced in English is neither seen as perfect nor unreliable; instead, it sees the New Testament as living. The English translation of the New Testament is not living in the sense that the foundation upon what it’s based is changing or growing; it’s living in the sense that translators, archaeologists, historians, and textual critics are still working to get closer and closer to the original wording in every place within the New Testament. Throughout church history the work of these people has helped us today to be as close as we’ve ever been to what was originally written by those like Luke and John. The necessary consequences of this continued work is an English translation that requires updates every so often. When additional information is discovered that brings clarity to the text of the New Testament then the only responsible thing to do is to go with those clarifications because honest historical, text critical work is always a support to the Kingdom of God.

A Necessary Consequence: The Woman Caught in Adultery

The excellent work being done to bring us closer and closer to the original writing of the New Testament means that there will be changes to what some have grown accustomed to reading in their English translation. By way of example, consider with me the regularly-retold story of the woman caught in adultery in John 7:53-8:11. This story shows up everywhere. It’s in movies about Jesus, articles about the gospels, children’s storybooks about Jesus—it’s a remarkable story showing the compassion and love of the Lord in standing up for this woman, being honest with her, and not condemning her because of her sin.

There’s just one problem: John, as a part of his gospel story, probably didn’t write it.

“The earliest manuscripts and many other ancient witnesses do not have John 7:53-8:11. A few manuscripts include these verses, wholly or in part, after John 7:36, John 21:25, Luke 21:38 or Luke 24:53.” The wonderful thing about this is that it’s not a secret; the quoted section above comes right from the New International Version (NIV2011) Bible in John’s gospel once you get to John 7:53. And this type of note isn’t unique to the NIV2011; most modern versions of the Bible will indicate this note either by having this section of John’s gospel in italics or by putting parentheses or brackets around the text.

Now, this does not mean that the conversation/confrontation between Jesus, the adulterous woman, and the Pharisees did not happen. It does mean, however, that (as far as we’re able to currently know) John did not write it when he wrote his gospel, which is hugely important if we want to rely on what the original writers wrote as our foundation for what God said.

Does this mean anything and everything in the New Testament is up for grabs? Could we be wrong about John 3:16-17, Romans 8, or Revelation 21-22? The radical skeptic would answer in the affirmative but the one who rationally looks at the evidence we have must conclude that we can and are certain about the text of the New Testament precisely because we’ve gone where the evidence has led.

Still, the question may remain: How can this be?

1,000 Piece Puzzle

Suppose you sat down on some lazy Saturday afternoon to work on an old 1,000-piece puzzle you have stuffed away in a closet. The problem with this puzzle, though, is that it’s not in a box; it’s in a plastic bag because the box has long since been lost. This means you don’t have a picture to use as your guide as you work on the puzzle. Is this a huge problem? Maybe yes, maybe no. Let’s suppose you decide to work on the puzzle even though you don’t have the box with the picture.

After a few hours of work, you discover that, even though you’ve used all the puzzle pieces, you haven’t completed the puzzle; in fact, you’re short about 50 pieces! Depending on the location of those missing puzzle pieces; it could be a big problem.

Now, let’s suppose we have the same situation with same puzzle in a plastic bag with no box. However, this time, after a few hours of work, you discover that you’ve completed the puzzle, but you have pieces remaining! In fact, after counting them up, you find that you have 50 puzzle pieces remaining. What kind of a problem do you now have? The problem is not that you don’t have enough pieces to complete the puzzle; the problem is that you need to decide which pieces don’t belong and thus need to be removed to make room for the remaining pieces that do belong.

Moving Forward in Confidence

The story about the puzzle with 50 extra pieces is similar to the situation that exists with the New Testament. This means that when you consider the reliability and authenticity of what was originally written compared to that of your English New Testament, you should see it as a translation built upon extra puzzle pieces; not one based on pieces that are missing.

When you’re reading your New Testament in your favorite modern translation (NIV, ESV, NLT, NASB, CSB, etc.) and you notice footnotes, brackets, and/or parentheses with explanations about earliest manuscripts you can know with confidence that what was originally written is either found within the verses or in the footnotes.

Granted, a couple of small sections of the New Testament have been discovered to be less than authentic throughout the history of the church but, again, this problem highlights the situation of there being too many pieces; not too few.

The New Testament may be a living text but that by no means suggests that it is an unreliable text. Trust the words of the New Testament and, therefore, trust the God about whom they testify.